What in the west do we know of Libya?

That somewhere in the North of Africa an insane dictator, the mad dog Colonel Ghadaffi, oppressed his people until they rose up and butchered him in the streets? Or perhaps we remember the Benghazi attacks when American officials died under sustained artillery attacks back in 2012? The more attentive among us may recall the start of last year when ‘warlord’ Khalifa Haftar laid siege to the western capital of Tripoli. When Libya breaks into the international consciousness it does so only as a story of Arab barbarism, the complexities of a nation fighting to define its future are hidden behind the smoke of so many mortar rounds.

The North African region has a long history as part of numerous civilisations, but Libya as a nation was formed first as an Italian colony in 1911. Later it was divided among the French and British before it gained independence as its own kingdom under the rule of Idris I in 1951. His rule lasted 18 years until a barely competent plot by a young Ghadaffi managed to oust the first and only king of Libya.

The modern story of Libya begins where Ghadaffi’s ends – the Arab Spring of 2011. In the coastal city Ben Arous, Tunisia, a street vendor named Mohammed Bouazizi set himself on fire in an act of protest against his local authorities. No one could have predicted that the fire he started would spread as a wave of protests across the Arab world, which would topple dictators in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, and Libya.

In Libya, the revolution turned quickly into civil war, with Ghadaffi loyalists on one side, and the rebels organised as the National Transitional Council (NTC) on the other. NATO rushed to back the NTC and provided extensive military support (~20,000 attacks, including ~7,500 airstrikes) which led to the capture and murder of Ghadaffi.*

This story is an easy sell, a maniacal dictator finally removed by the democratic will of the people, helped by the ever benevolent west.

Near the site of the fighting, rebels dragged a wounded and bloody Ghadaffi was from a sewage pipe.

“He called us rats, but look where we found him.” One NTC fighter told a Reuters journalist. Fuzzy camera footage from this moment shows the dictator pleading for his life. Hours later the Colonel died of gunshot wounds in an ambulance.

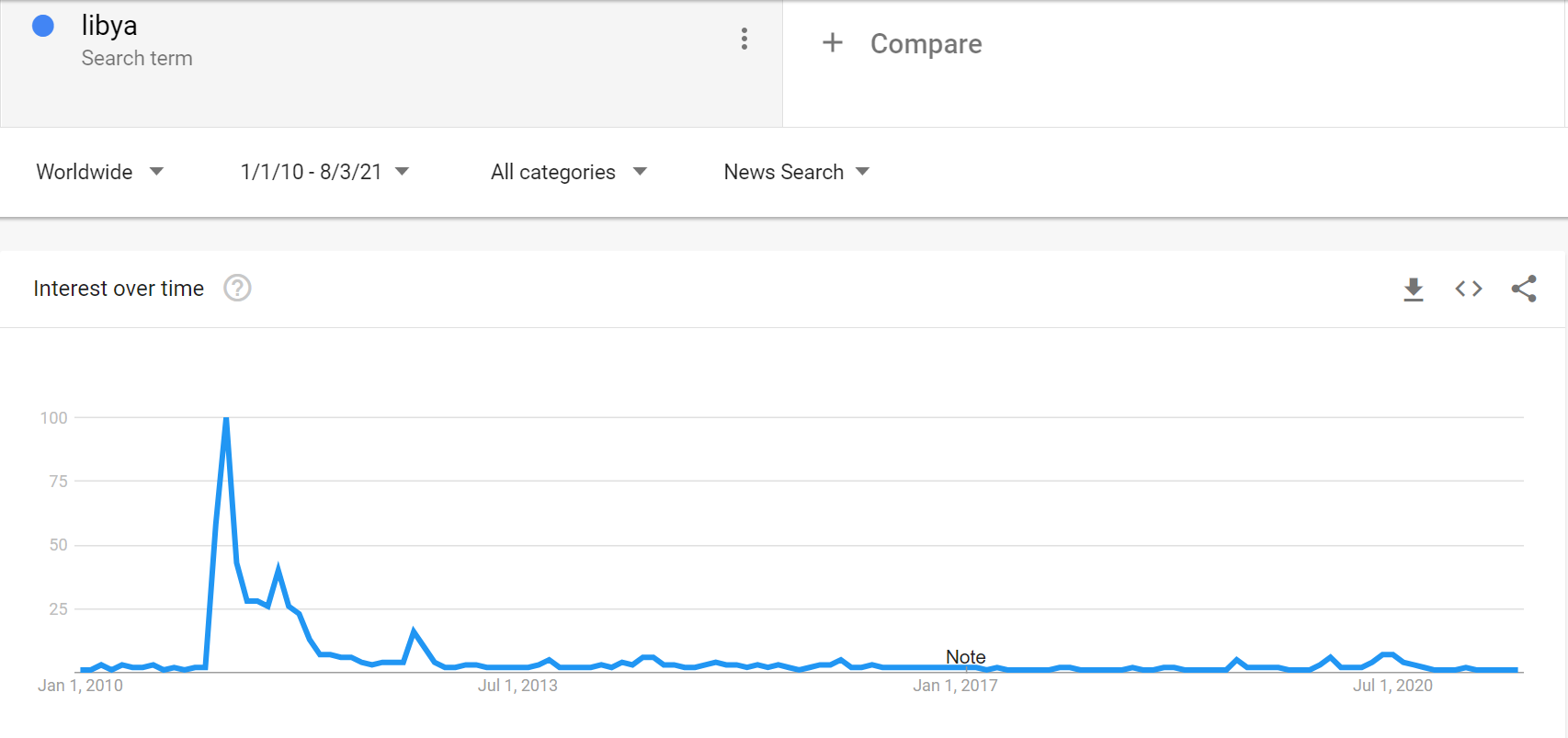

But from this moment forward, the Libyan story becomes too complicated for much of the international press. Without a Manichean struggle between secular democracy and Islamic socialism, Libya’s history continued, with dramatically less international attention.

The ten years since Ghadaffi’s death are not an easy story to tell, and excessive use of initialisms is unavoidable, I have therefore attached a glossary of different organisations.

The NTC, having emerged victorious, set out to form a democracy. In 2012 Libya held its first election. The NTC gave way to the new liberal-dominated General National Congress (hereafter GNC). For two years, it looked like it might just be a success story for the Arab Spring, NATO and global democracy.

For those two years the GNC held Libya together, but the cracks were barely hidden beneath the surface. The fatal blow came in 2014 when the GNC held elections to create a legislative chamber known as the House of Representatives. With just 18% voter turnout the Supreme Constitutional Court annulled the election, effectively declaring Libya’s legislative body to be an illegal organisation.

The House of Representatives, however, refused to disband, instead, it separated itself and relocated to the eastern city of Tobruk. Once there it aligned itself with the “Libyan National Army” (LNA) a collection of armed forces which are the dominant military power in the east of Libya. The House of Representatives combined with the LNA was a sufficiently large power base to rival the GNC’s claim to be the legitimate rulers of the country. In 2015 the House of Representatives appointed the now-infamous Khalifa Haftar to be the head of the LNA.

Libya then had two governments, two armies, and no clear path forward.

In an attempt to reconcile the two governments, the United Nations brought them together in an uneasy alliance. Known as the Government of National Accord (GNA) this was supposedly a unity government that established itself in Tripoli at the end of 2015. The alliance fell apart in short order, with the Tobruk-based HoR officially renouncing the GNA in the summer of 2016. Despite having only some backing from the old GNC and none from the House of Representatives, UN backing allowed the “unity” government to carry on existing even as the governments it had unified left.

Meanwhile, the GNC was also falling apart, a large number of the Islamist politicians within had splintered to declare themselves the “Government of National Salvation” with support from the Muslim Brotherhood. The Government of National Salvation tenuously held territorial control of Tripoli between 2014-2016. What remained of the GNC absorbed itself into the GNA under the new title “High Council of State”

2014-2016 was a period of political upheaval, fragmentation and uneasy alliances. Underscored at all times with outbreaks of military conflict between the rival heirs to the Libyan revolution. It was a bewildering process, but by the summer of 2016, only two factions were wielded enough power to credibly rule Libya:

The UN-backed GNA ruling from the west, and the LNA aligned House of Representatives ruling from the East. So set was the stage for the main period of what has come to be known as the Second Libyan Civil War.

The international community by this point was divided between Haftar and the GNA. The UN obviously supported the government it had helped create, any many countries fell in line including the United States, the United Kingdom and most of the EU (Excluding Greece, Cyprus, and France)

On the other side, Haftar received backing from a diverse group, notably Egypt, France, Syria, the UAE, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and though Haftar greatly denies this – Israel.

HoR vs GNA was the main nexus of conflict, but there were (and are) thousands of local militias representing tribal, theological, and political interests. As well as the aforementioned Government of National Salvation, various coalitions of Islamist militias rose and fell throughout the war and, as they so often do, Daesh grew like weeds in the cracks of power.

The conflict reached its Apex when Haftar’s forces launched the largest offensive of the war in 2020, moving out from their eastern power base, and advancing on Tripoli at rapid speed. Having largely defeated Daesh in the east, Haftar’s LNA looked set to destroy the GNA. And it might have done just that, but Turkey, a new ally of the GNA pushed Haftar back with a mass airstrike campaign. The LNA had no choice but to retreat. This defeat, combined with crippling debt and sanctions have forced the LNA+HoR back to the negotiation table and on the 24th October 2020, a permanent ceasefire was declared, effectively ending the war.

Generously, we might excuse the lack of attention paid to this historic moment by way of attributing it to the overwhelming complexity of the conflict. But if that were so, then why did Haftar’s advance on Tripoli generate a surge of media attention when a national peace deal failed to do the same? If we care for the suffering of Libyans we ought to care too for their peace.

Now in 2021, we may be approaching a lasting peace. The GNA and the LNA have come together to form a new government: the Government of National Unity (GNU). Elections are scheduled to be held in December this year. In exchange for Haftar’s support, GNU prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah has agreed to pay off the LNA’s debts to the tune of 3 billion Libyan Dinar, approx 664m USD. One major obstacle is a growing sense that the LNA may not be completely loyal to Haftar since his failed offensive, continued violence in the streets of Benghazi since the ceasefire indicates Haftar’s ability to reign in his forces may be slipping, if the LNA falls apart so too could the fragile peace.

However, at the time of writing Dbeibah is preparing to travel to Benghazi, hoping to sign a new national budget with Haftar. There are many pitfalls, and Libya is far from settled but for the first time in a long time, there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

*Officially, NATO involvement did not have the legal mandate to target the dictator, and has maintained it was not their intention to decapitate the Libyan state. What we know is that in the final rebel push against Ghadaffi’s home city of Sirte, Oct 2011, NATO forces intercepted a phone call made by Ghadaffi – shortly thereafter an RAF Tornado completed a reconnaissance mission which identified a convoy of 75 cars fleeing the rebel advance. After the reconnaissance was complete an American predator drone commenced an attack on the convoy, it was joined in short order by French fighter jets. Much of the convoy was destroyed and NTC ground forces were rapidly on the scene engaging in conflict with the now splintered convoy. Footage then shows a wounded Ghadaffi pleading for his life. He died shortly afterwards in an ambulance.

Glossary:

- NTC: National Transitional Council – the collective banner of revolutionaries in the fight to depose Ghadaffi

- GNC: General National Congress – the government elected by the NTC first in 2012

- HoR: House of Representatives – formed by the GNC but quickly turned on the Congress to join the LNA

- LNA: Libyan National Army – collected forces led by Khalifa Haftar

- GNA: Government of National Accord – UN-backed Government throughout the civil war

- GNU: Government of National Unity – Government formed in early 2021 bringing peace to Libya

- Daesh: the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in Libya