Three years ago, swathes of Hong Kong’s people enacted mass protests. What began as demonstrations against an extradition bill grew into broader opposition to Beijing’s increasing power over the supposedly autonomous region. In the years following, the protester’s demands have not been met, and the repercussions have been severe.

Hong Kong’s autonomy from China is precarious resting as it does on an agreement between Margaret Thatcher and Deng Xiaoping, that Hong Kong will be part of China, but govern itself until 2047. Officially this “one country, two systems” doctrine has held, but in practice, the promised autonomy has been steadily eroded.

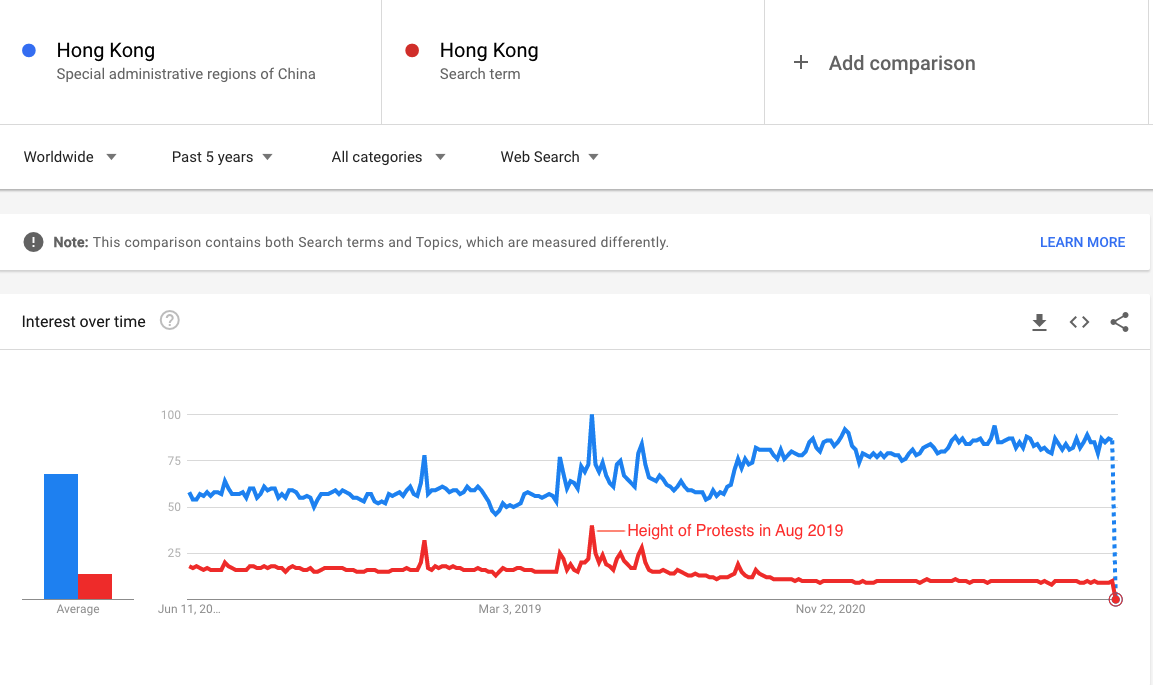

The protests against Chinese rule quickly drew international attention. However, as the protests came to their conclusion, interest in the western media dropped off and the state backlash has not been ignored in English language media.

The tornado-causing butterfly flapped its wings in a hotel room in Taipei. There, in 2018, a 19-year-old Hong Kong citizen, Tony Chan Tong-kai, strangled his pregnant girlfriend Poon Hiu-wing to death. He took her body and hid it in the bushes by the Tamsui River.

Chan then fled home to Hong Kong, where he confessed to his crimes. Despite his admission, he could not be arrested for the murder because without an extradition treaty between Hong Kong and Taiwan, there was no way to bring him to justice.

The proposed solution became the disputed “Extradition Bill”, an amendment that would allow Hong Kong to send its citizens for trial in Taiwan, Macau and, crucially, mainland China. This would have opened a back door for Hong Kong citizens to be subject to Chinese criminal prosecutions. The proposal came first from Hong Kong’s Security Bureau, a government agency that is responsible for “law and order”, a suitably vague mandate that encompasses policy, policing, prisons, and immigration. The head of the Security Bureau at that time, John Lee Ka-chiu, has since become infamous.

In March 2019 thousands marched on the government headquarters, this was the first wave of seven months of protests which enjoyed mass support from Hong Kong’s people. Protest organisers claim that at the height of August 2019 1.7 million people, nearly a quarter of the population marched together. Calculations of protest numbers are politically contentious, and work such as this Rueter’s investigation can be useful in assessing crowd sizes. However, faced with violent reprisal from police, protest turnout is not an accurate measure of popular opinion.

Local election results from November 2019 are a less coerced measure and show vast support across the region for the protestors and their struggle against Beijing-backed authoritarianism. The electorate delivered a 90% landslide victory to pro-democracy candidates.

With popular backing and growing expertise in protest tactics, protesters became a black-clad force to be reckoned with. In a year which saw waves of protests around the world, Hong Kong was a tsunami.

One clear victory for the protestors was achieved when on the 23rd of October the proposed extradition amendment was scrapped, fulfilling the first demand the protesters had made. However, it was too little too late. By October the protesters had broadly agreed on four other demands:

- For the protests not to be characterised as a “riot”

- Amnesty for arrested protesters

- An independent inquiry into alleged police brutality

- Implementation of complete universal suffrage

As for these demands, it is striking how almost the opposite has occurred in every case. The protests are continually called riots by those in charge, arrests continue for participants, and the “independent inquiry” has been lambasted as police apologism by Amnesty International.

Worst of all John Lee has now been chosen by a Beijing-stacked electoral commission to succeed Carrie Lam as the new Chief Executive of Hong Kong. As secretary for security, Lee oversaw the extradition bill, and then led the crackdown on the protests against it, his appointment is antithetical to a free future for Hong Kong.

Although the protests eventually led to the scrapping of the extradition bill, the national security law was established in June 2020. In essence it is a declaration from Beijing: ‘If you won’t come to Beijing for the law, then the law of Beijing will come to you.’ For China, it was a way to ensure the existence of a legal framework to resolve challenges to its authority. The law was passed in secret, its 66 articles hidden from the public until confirmation.

Fundamentally, the law now criminalises secession or subversion which it defines as terrorism, collusion, or any act that undermines the power of the Central government. These crimes are punishable with a maximum sentence of life in prison

The law also introduces a new security office directly controlled by the central government with no influence from the local powers. Hong Kong is the only common law region in China, and the National Security Law threatens to further dissolve its independent judicial power. Interpretation of the law will lay solely with Beijing, and if any conflicts arise with Hong Kong’s law, Beijing takes priority and trials may be behind closed doors.

The law also allows for the surveillance, detainment and search of any persons with the permission of the Chief executive. The familiar justification that every action is in the name of stability remains uncompelling.

In 2047, Hong Kong, whose people have gone to extreme lengths to reject Beijing’s rule, is set to officially join the mainland, this date will be a clash between the forces of authoritarianism and the will of a people to determine their own fate. It remains to be seen if there will be retribution for Jinping and his surrogates. There is only one certainty for Hong Kong and that is the certainty of reckoning.

E. Martin